What do the Brooklyn Nets need as they head into what Jordi Fernandez calls their “Summer of Our Lives?” How about an offensive? ANY offense.

The six worst teams in the NBA this season had one thing in common: all scored less than 112 points per 100 possessions. (The only team in that range to make the playoffs was the Magic, thanks to their second-best defense.) Your Brooklyn Nets had the third worst offense in the league, scoring just 108.1 points per 100 possessions. It’s safe to say that their quest for “sustainable success” will have to begin with figuring out how to score.

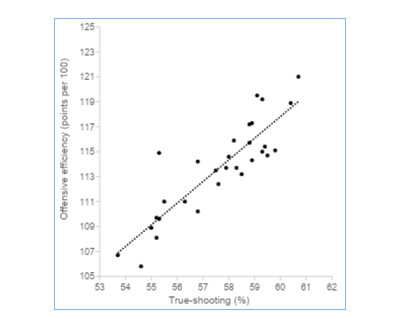

The only near-absolute requirement for a good offense is good shooting. Across the league, teams’ offensive efficiency was very strongly related to their true-shooting percentage, a weighted combination of FG%, 3P%, and FT%. The NBA’s best offenses—the Cavs, Celtics, Thunder, and Nuggets—were all excellent shooting teams, while the laggards—the Wizards, Hornets, Nets, and Magic—had the four lowest true-shooting percentages in the league.

Alas, the Nets’ prospects going forward are even worse than they appear here because three of their five above-average shooters—Dorian Finney-Smith, Dennis Schroder, and Shake Milton—were traded during the season. The team’s TS% cratered once they left, from a league-average 57.7 before the trades to a woeful 53.7 after. The only proven shooter returning (maybe?) next season is Cam Johnson, whose 63.2 TS% was more than five points above league average. (Dariq Whitehead was only slightly above league average, and he played just 20 games.)

It would be comforting to assume that the Nets’ terrible shooting will automatically improve with better point guard play, but that’s not necessarily the case. Trae Young and Cade Cunningham were All-Star point guards and among the league’s leaders in assists this season, but their teams were just average shooting teams. The Warriors had the NBA’s highest percentage of shots assisted—and the greatest shooter in NBA history—yet they ranked 21st in true-shooting. On the other hand, the Bucks were one of the hottest-shooting teams in the league despite ranking just 22nd in assists per 100 possessions and 23rd in assist percentage.

The only team in the league to score substantially more than their mediocre shooting would have predicted was the Houston Rockets. They were the most determined practitioners of a very different offensive style, heavily reliant on physical, opportunistic play. The Rockets led the league in offensive rebound percentage (36.3; the league average was 29.3) and in the share of their points coming from putbacks (15.8; the league average was 12.4). Points in the paint, fast break points, and points off turnovers were additional hallmarks of this style, and the Rockets were above average in all three.

The antithesis of Houston’s physical offensive style was Boston’s remarkable 3-point barrage. The Celtics took almost 54% of their field goal attempts from beyond the arc. (The next highest percentage in the league was Golden State’s, almost seven points lower.) The Celtics were not an especially efficient 3-point-shooting team, less than 1% above league average, but they made it up on volume, producing the second-most-potent offense in the NBA.

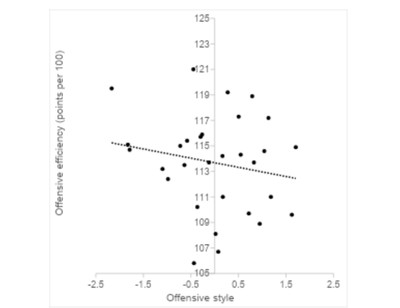

The Celtics success might seem to suggest that hoisting threes is the most efficient way to score in the modern NBA; but the reality is more complex. Across the league, there is no relationship at all between three-point attempt rates and offensive ratings. Arraying teams by offensive styles, from the 3-point-heavy Celtics on the far left to the physical, opportunistic Rockets on the far right, begins to show why not.

Four of the league’s top six offenses fell closer to the Rockets’ style than to the Celtics’. The Nuggets took the fewest threes in the league (less than 35% of their shots), but they led the league in points in the paint and fast break points (48% and 17% of their scoring, respectively). They also ranked fourth in the percentage of their field goals that were assisted, thanks to all-world point-center Nikola Jokic.

The Nuggets’ offensive recipe is probably not one that can be replicated. However, the Grizzlies—the NBA’s original “Grit ’n’ Grind” team—provide another example of a successful offense built less around 3-point shooting than around scoring in the paint, offensive rebounds, and putbacks. The Knicks had similar success by scoring inside and limiting fouls and turnovers.

The best offensive team in the NBA, the Cavs, fell near the middle of the distribution of offensive styles. Their 3-point attempt rate (almost 46%) was fifth in the league, and they were second best in 3-point accuracy (bested only by the Bucks). But they were also above average, or only slightly below average, in offensive rebounds, steals, points off turnovers, and points in the paint. They played both of the league’s two primary offensive styles effectively.

Conversely, the worst offenses in the league tended to fall in the middle of the distribution because they did nothing well. The Nets, for example, were third in the league in 3-point attempts despite establishing a new franchise high, but 25th in 3-point accuracy. They weren’t very physical or opportunistic, either. They committed the most fouls in the league, but were below average in scoring in the paint and just about average in offensive rebounding, second-chance points, and fast break points.

It is hard to make even an educated guess about what the Nets’ offense might look like going forward. That will depend on who they manage to add through the draft, trades, and free agency in the next 15 months—and who they lose.

If Cam Thomas continues to lead the team in usage, can he score more efficiently? Thomas improved his shot selection this season, reducing his mid-range shots from 30% to 25% and increasing his 3-point attempts from 33% to 43%; but his true-shooting percentage was still just average, 57.5%.

What about Cam Johnson? If he remains with the team, can he replicate this season’s hot shooting (true-shooting almost three percent above his career rate)?

The Net whose job may be most secure at the moment is coach Jordi Fernandez. Does he have a preferred offensive style? He has talked about relying on analytics and “challenging” his players to shoot more threes, but has also preached “physicality” and “Brooklyn grit.” Perhaps he, too, would be happy with a team that has any offensive style at all.